Are you a socialist? Take the test….

A 2011 study yields surprising results.

The word “socialist” was, for all intents and purposes, dead and buried after the fall of the Iron Curtain. But it has enjoyed a huge resurgence in popularity since, oh, 2008 or so. The thing is, since we hadn’t had any real socialistm for awhile, our understanding of what the term means has gotten a little fuzzy.

So the question is, how socialist are you really? Maybe none at all, maybe a whole lot, and maybe somewhere in the middle. Let’s find out.

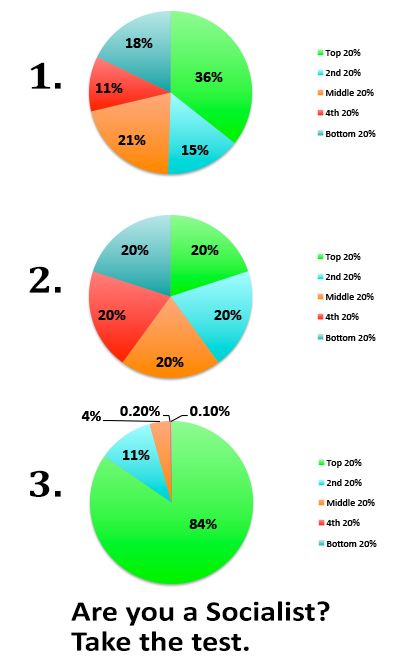

Below is a series of three pie charts, each depicting the relative income distribution of a hypothetical nation. It’s color coded so as to reflect what percentage of the nation’s total wealth is owned by each quintile of the population (that’s a statistical term that means “fifth” – so the top quintile, shown in green, is the top 20%, or the richest fifth of the population. The bottom quintile, in dark blue, is the poorest 20%). Make sense? Good.

I’m going to ask you to decide which nation you’d rather live in. Here’s the catch. You’re going to be dropped randomly into the distribution and you have no control over where you land. You have a 20% chance of winding up in the top quintile and an equal chance of being in the bottom quintile. Obviously landing in the bottom quintile means different things in each of the three nations.

So, here are your three hypothetical nations. Which one would you rather be plunked down into?

Now, there’s not a right answer. This is about understanding ourselves, not judging or telling people they’re wrong. And I’m not keeping score. We’re on the honor system and I trust you to be honest with yourself. You don’t have to report your decision to me or anyone else.

Now, there’s not a right answer. This is about understanding ourselves, not judging or telling people they’re wrong. And I’m not keeping score. We’re on the honor system and I trust you to be honest with yourself. You don’t have to report your decision to me or anyone else.

This is a fun little exercise. It was concocted by Michael Norton and Dan Ariely of Harvard and Duke, respectively. They administered it to more than 5,500 Americans and published their results in 2011. What they found was perhaps surprising.

For starters, only one of the three nations above is actually hypothetical – that would be #2, where the money is distributed evenly. Nation #3, where the top 20% of the population holds 84% of the wealth, is the United States. Nation #1, where the green 20% holds 36% of the money, that’s Sweden.

#1 is an idealized socialist paradise where everyone is equal. Sweden is considered by many to be one of the world’s most prominent socialist societies. As you can see, it’s hardly a perfect example of socialism, but you do have a far more equal distribution of wealth than you have in places like the US.

So, what did Norton and Ariely find? 47% of participants selected Sweden and another 43% chose the hypothetical perfect distribution. Only 10% preferred the US. Head to head 92% preferred Sweden to the US.

How did you answer?

This study is meaningful, of course, because it indicates that a lot of people who say they detest socialism (whatever they think the word means) actually don’t. When faced with the question of what kind of system they’d rather live in (assuming they don’t get to pick their status), a staggering majority of our fellow countrymen – over 90% – choose the socialist option.

No, you’re not automatically a “socialist” if you picked #1 or #2. As much as we love to rely on cheap labels, the truth is that being socialist or capitalist or whatever is a lot more complex question. We don’t live life by picking abstract forced choices like these and as I have noted in comment threads elsewhere, social research methodologies are often problematic.

That said, while your answer on this quiz doesn’t tell us everything, it damned sure tells us something. Whether it’s a deep-seated response to income inequality that you don’t think about very often or maybe a certain calculating approach to risk management, if you, like a vast majority of those in the study, picked either of the first two answers, it means that something about systems that distribute wealth in a more egalitarian fashion makes sense to you, at some level.

I believe the study’s results also hint at something very useful in our national character. It’s one thing to identify with the haves against the faceless, stereotypical have-not horde when we believe we have some control over our destiny. But when faced with a blind draw, we make a very different decision. Fine. But what it also suggests is a path through the sound and fury and hateful rhetoric to a point of human empathy. If we don’t want to take our chances on that dark blue section of the American pie chart – and who in their right mind would? – doesn’t this translate into a way of thinking about the actual have-nots in our midst?

I have to think on this question some more. I hope you will, too.

Nice.

I selected the idealized distribution because I was looking at it as a wager and hedging my bets. Now I have to really think about what that means though, because I’m not actually a Leveller, but maybe the people who have been accusing me of being a socialist all these years actually have a point. Maybe I should just think really hard about what sort of socialist I am and own it.

Head to head, if you ask me to choose between the two distributions that actually reflect real countries, I’ll choose Sweden’s distribution every time.

The combined share of the middle 60% in distribution #3 troubles me as much as the share of the bottom 20%, and I would love to see that top 20% broken down further.

This is why major news organizations rarely hire terriers for the copy desk. Thanks for the catch.

As for the rest, yeah, I’d hardly offer this up as anything like conclusive proof that 90% of Americans are secret socialists. But as I say, it certainly tells us something interesting. At the absolute minimum, I think we can say that when confronted with radically different income distribution models and asked which they’d rather be airdropped into at random, they instinctively prefer the ore equitable distribution.

This is an abstract result, not an applied one. But it illustrates something important about how our ideology works. Many Americans have been seduced into believing that black is white, up is down, wet is dry, rich is poor, etc. They have been encouraged to believe that they really believe in something that they don’t believe in.

The Marxist term for all this is “false consciousness,” and I think the challenge that those of us on the outside face isn’t how to move the population to the left, but how to open everyone’s eyes. If I had a magic wand and could use it to simply make the public see the political economic dynamics for what they are, I’d not have to worry about parties or ideologies anymore. There probably aren’t 20 people in Washington who’d win re-election and depending on the general mood that day we might even have a few heads parading around the Mall on pikes.

I do not advocate violence, but I can also see how this might have certain positive effects on the thinking of future would-be corrupt pols.

I have to think about this a bit, Sam. I think I agree with most of it. What I see, in the here-and-now, is an economic system that is so badly out-of-balance that it cannot possibly be sustained, unless we adopt some sort of postmodern feudalism. When I think about this stuff at all, my first concern is to engineer some sort of solution that does not involve mobs. Mobs are bad for everyone.

Honestly, I don’t study it very closely, because there is not very much I can do about it, and it seems to be headed in the direction of a no-win scenario.

great post

Two points: first, the answer to this test offered by a reasonable person ought to indicate that he’s indifferent among the three scenarios posited, because what actually matters is the amount of wealth each individual possesses in absolute terms; i.e. whether individuals have enough to satisfy their own needs. Using a pie chart only shows the relative wealth of people with respect to each other, which is essentially irrelevant. The scenario in which each quintile has an equal share of the aggregated wealth might well be one in which everyone is doing very poorly, and the scenario in which the top quintile owns 84% of “the nation’s wealth” might be one in which even those in the bottom quintile have more wealth than they could ever use. Without absolute numbers, these distributions are meaningless.

Second, and more fundamentally: the entire premise of the study is invalid. It posits that there’s such a thing as “the nation’s wealth”, implying that wealth originates in an pre-aggregated pool, and is then distributed out to disparate persons, with some of them unfairly claiming a greater share than others. But in reality, there’s no such thing as “the nation’s wealth”. Tthere never was any pre-aggregated pool of wealth; instead, everyone develops their own wealth through their own endeavors separately from each other: in other worlds, all wealth originates with someone in particular already owning it, and it never even subsequently gets aggregated into a single pool. Everyone owns 100% of their own wealth and 0% of “the nation’s wealth”.

What this study does is to measure everyone’s separate wealth, add all those measurements into a single aggregate sum, and then measure the proportion of that sum that each person’s wealth accounts for. But the sum itself doesn’t represent anything that empirically exists; it’s an aggregation of quite separate measurements, and makes little more sense than adding up everyone’s shoe sizes into a single sum.

This is a very poor study that uses artificial metrics that represent nothing valid to mislead people into making statements based purely on vague emotional inclinations, but then dresses those judgments up in the language of quantitative rigor.

Second, and more fundamentally: the entire premise of the study is invalid. It posits that there’s such a thing as “the nation’s wealth”, implying that wealth originates in an pre-aggregated pool, and is then distributed out to disparate persons, with some of them unfairly claiming a greater share than others.

Thank you for the archetypal, catechismic neo-liberal dogma example.

Quite happy to provide it. It’s a shame that certain ideologies have managed to incorporate empirically valid observations into their dogma, as it makes those observations somewhat easy to dismiss without any substantive consideration, but those observations bear repeating all the same.

Of course, where this topic is concerned, every point is *someone’s* dogma: I’ve never actually heard anyone offer a substantive justification of the “nation’s wealth” concept, either, so here, at worst, the discussion simply amounts to one dogma contradicting another.

Sorry, but no. You’re twisting valid statements about collective economics into something that serves prefabricated ideological ends. And you never will hear “substantive justification of the “nation’s wealth” concept” because pure ideologues reject anything that doesn’t fit their cant.

If you’d like to engage the substance of the post in good faith, do so. Otherwise move along. As is, you have nothing to say that we can’t copy and paste from a million other places.

Pure ideologues tend often to insist upon things that can’t be justified on their own merits; I’m rejecting only what doesn’t fit my observation of reality, building what you call an ideology out of actual experience rather than putative Platonic universals.

If you’re going to posit such a thing as “collective economics”, treating the patterns that emerge from the dynamic and diverse complexity of human beings’ independent behavior as a kind of organic unity that can be treated as a single coherent thing unto itself, I’d love to hear the explanation. I’ve also seen these concepts posited by many sources, none of whom seem ever to attempt to substantiate their position, but merely to stipulate it.

What is the empirical basis for the concept of “collective economics”, as you call it? Apart from the all-too-common arguments that invert cause and effect, and treat high-level emergent patterns as the cause rather than the consequence of individual human behavior, what substantiates regarding an “economy” as a singular thing rather than a vast plurality being viewed at too great a distance to make out the separateness of its elements?

Pure ideologues tend often to insist upon things that can’t be justified on their own merits; I’m rejecting only what doesn’t fit my observation of reality, building what you call an ideology out of actual experience rather than putative Platonic universals.

“Faith,” in other words.

Exactly. Why rely on faith, when we can rely on direct experience of the external world?

Which is the opposite of what you’re doing.

As I said, if you want to engage with the substance of the post, please do. Otherwise, move on.

But what I see happening here is that you’ve posited an abstraction (“national wealth”) as the basis for an argument, and I’m questioning the empirical validity of that abstraction on the grounds that I don’t see anything observably corresponding to it in the external world.

I don’t mean to be rude in saying so, but I regard the “faith” claim as being the one that posits abstractions with dubious empirical basis, and the “skeptical” claim as being the one that challenges them, and asks for substantiation.

I hope that I am reasonably engaging with the substance of the post by questioning its underlying assumptions.

Asterisk

OK, I’m a Univ of Chicago trained MBA, and I too sometimes don’t quite trust Sammy’s interpretion of economic theory, e.g., his understanding of how labor markets work falls short. However, I think your arguments are a little off the mark.

First of all, there clearly is such a thing as national wealth. That’s why people immigrate from poor nations to rich nations. As the recruiters from the I-banks used to say, “There’s so much money sloshing around in big deals that you can get very, very rich from what spills over the edge of the bowl.” In wealthy economies, more money is sloshing around. That’s why it’s better to be born lower middle class in the U.S. than upper middle class in Sierra Leone.

Second, there’s no implication in the study that the wealth comes from being pooled and is there to be redistributed. This is nonsensical Randian paranoia. You might have read that, but neither the study nor Sam’s piece wrote it.

Third, both absolute wealth and relative wealth matter at the individual level. To your point, absolute wealth clearly matters. Someone recently wrote a very good editorial about why the U.S. poor aren’t up in arms about the concentration of wealth and posited that perhaps it’s because being below the poverty line in America still isn’t that bad a gig–you still get a refrigerator, cellphone, roof, food, and car. (Did I see that here?)

However, relative wealth also matters. For better or worse, people judge their own well being by what their neighbors have. What do you covet, Clarisse? What you see. To argue otherwise is asinine.

At any rate, the point of the study isn’t even about economics. It’s about the fact that people don’t really understand the implications of what they’re saying much of the time, e.g., when most people in the US are against Obamacare but for the Affordable Care Act, or against government intervention in healthcare but for Medicare, or against wealth redistribution and socialism but for Social Security. Or against federal government power but blase about the NSA scandal. Or as in the case of some recent Western governors, against the role of the federal government but for disaster relief for ranchers.

.

Otherwise

Ahem. his understanding of how labor markets work falls short. This is true if – and only if – we accept the idea that how things are is how they naturally must be. There’s a lot of question-begging in that assumption. I’m down with the rest of your reply, though.

I’m also an MBA, BTW, and I can’t agree with you via interpreting the pool of available opportunities as somehow an instance of Sam’s concept of “national wealth” – when people immigrate from one area to another in search of greater opportunity, they’re doing so in order to be in a position to form economic relationships with the other specific parties in their new place of residence. But all of the wealth that exists in that context still belongs to specific, identifiable parties; there’s certainly a network effect in action, where people tend to position themselves and their wealth in ways that are conducive to their further prosperity, but a network effect is a bottom-up emergent pattern, not a singularity. We can describe the extent that disparate parties’ wealth forms coherent patterns in relation to other parties’ wealth, but that’s not at all the same as “national wealth” in the sense that the original article invokes the concept.

Secondly, it’s not that there’s some implication of pooled wealth in the original argument – it’s that this is a fundamental premise necessary for the concept of “distribution of wealth” to have any meaning. Without such a premise, what sense can you make out of aggregating everyone’s separate wealth into a single sum, and then seeing what proportion of that aggregate sum each person’s wealth accounts for? What does that sum actually represent in the real world? Without invoking these concepts, how does it make any more sense than adding everyone’s shoe sizes together and seeing what proportion of the total sum each person’s shoe size accounts for?

You need to posit some qualitative relationship between people’s wealth in order for quantitative comparisons to have any meaning, and the method I most commonly see for positing such a relationship is to zoom so far out conceptually that all of the complex details and varied relationships that form economic patterns fade out of view, so that the whole blurred-together thing can be construed as a singular, consistent entity.

The other common argument is the one you mentioned regarding relative wealth. Of course, it doesn’t seem very compelling to say that relative wealth matters just because some people are prone to getting worked up when comparing themselves to others. People have a lot of other prurient compulsions and emotional complexes, too, but few of those are regarded as having the sort of legitimacy that this one in particular does.

> This is true if – and only if – we accept the idea that how things are is how they naturally must be.

Well, this is the core principle of science. We observe, and build models to represent the world under the tentative assumption that similar patterns will be observed under similar conditions in the future. I agree that the universe need not necessarily be consistent, but this way of thinking seems to be the best we have to go on given the constraints of human cognitive power.

The alternative would seem to imply yielding to pure conjecture, even when it’s untested or untestable, and, well – not intending to be too circular in my reasoning here – that hasn’t proven to be the most reliable methodology in the past.

By the way, Sam, I’d argue that we do have real socialism. If you look at the govt expenditures over total GDP of all the OECD nations, they’re in a relatively narrow band, and all involve extensive wealth redistribution. Even us, although we’re toward the low end once you back out military expenditures. The reason is, for better or worst, socialist democracies seem to be the most stable form of government in an AK-47 world and rulers like stability.